By Ben Tolkin

Great

question, but it will need quite a long answer! You're asking about

two of the most fundamentally

human activities: language

and

mathematics.

I'll start with letters.

Who invented letters?

For

most languages, there wasn't just one person who “created”

letters. (Though there are a couple of interesting exceptions I'll

talk about at the end!) The letters we use for writing English and

most European languages are slightly modified versions of the letters

used by the Romans for writing Latin. Those were based on earlier

Greek letters, which in turn came from even earlier ones... Almost

every modern writing system is descended from just a handful of very

early sets of letters.

Writing

was developed independently in at least two places: the Fertile

Crescent (modern-day Iraq) in 3000 BCE, and ancient Mesoamerica

(Central America and Mexico) around 600 BCE. The development of

writing in China in 1200 BCE was also probably independent, and its

development in ancient India and Egypt may have been as well. Other

than that, all parts of the world only started writing by borrowing

it from their neighbors; Europe, Central Asia, and Africa had writing

brought to them by cultural exchange, migration, or conquest.

The

most basic method of writing things down is pictographic: to

write about something, you just draw a picture of it. What makes it

writing, as opposed to just making art, is when you start

drawing not just objects, but abstract concepts represented by

symbols. The earliest writing symbols used a mixture of pictures and

symbols representing ideas. Let's say if you wanted to record that

you'd traded a bull to someone for two chickens, you'd just draw a

picture of a bull, two pictures of chickens, and some symbol

representing a “trade”. As time passed, these pictures became

more and more stylized, looking less and less like real objects.

These scripts are known as logographic or ideographic

writing systems; each symbol represents a word or idea.

This

saves time (it's easier to draw a symbol everyone knows stands for

“bull” than draw an accurate picture of a bull, every time) but

it made the pictures

hard to understand unless you'd been taught their meanings. If you

look at very, very old artifacts, you might

be able to make out some of the pictures,

but later systems like cuneiform

in

the Middle East, hieroglyphics

in

Egypt, and bone

script in

China don't really look like pictures at all.

|

| Akkadian cuneiform |

|

| Cursive Egyptian hieroglyphs |

|

| Chinese bone script |

It's

important to remember that for most of history, very, very few people

could read or write. These writing systems had

thousands

of complicated symbols, but the only people who had

to learn

them were professional scribes. Being able to read and write used to

be a full-time job!

Most

writing systems today are not logographic (some Chinese characters

are still pictures of the thing they represent, but most are not.)

Almost every language instead uses a phonographic writing

system, like an alphabet: each symbol represents a sound. (Other

phonographic systems include syllabaries, where each letter

represents a syllable, and abjad, where each letter represents a

consonant.) While a language might have tens of thousands of words,

they only have a few sounds, so alphabets are much easier to learn

than logographic writing systems. So who invented phonographic

writing?

Like many important inventions, it seems to have developed from interactions between different cultures. Ancient Egypt was a crossroads for many cultures speaking many languages, and Egyptian scribes needed a way to record all of them. One of these cultures was the Canaanites, a Middle Eastern group that spoke a language in the Semitic family (an ancestor of modern Hebrew and Arabic.) Egyptian scribes used a pictographic and logographic writing system called hieroglyphics to write their own language, but when recording the Canaanite language, they just used hieroglyphs to represent sounds: each consonant sound was represented by the hieroglyph of a word that began with that sound. For example, “house” was pronounced bayt in early Semtic languages (it still is in Hebrew today!), so whenever there was a "B" sound, scribes would just write the hieroglyph for “house,” a rectangle. The first letter of this alphabet was 'alp, a picture of a bull's head.

Like many important inventions, it seems to have developed from interactions between different cultures. Ancient Egypt was a crossroads for many cultures speaking many languages, and Egyptian scribes needed a way to record all of them. One of these cultures was the Canaanites, a Middle Eastern group that spoke a language in the Semitic family (an ancestor of modern Hebrew and Arabic.) Egyptian scribes used a pictographic and logographic writing system called hieroglyphics to write their own language, but when recording the Canaanite language, they just used hieroglyphs to represent sounds: each consonant sound was represented by the hieroglyph of a word that began with that sound. For example, “house” was pronounced bayt in early Semtic languages (it still is in Hebrew today!), so whenever there was a "B" sound, scribes would just write the hieroglyph for “house,” a rectangle. The first letter of this alphabet was 'alp, a picture of a bull's head.

Believe

it or not, those Egyptian hieroglyphics are the ancestors of the

letters you're reading right now! 'Alp and bayt eventually

turned into the Alphabet, and if you know what to look for, you can

see traces of the original hierogylphs in letters today (don't think

the letter “A” looks much like a bull's head? Turn it upside

down!) The Canaanite writing system was the basis for Phoenician, a

language spoken by sailors and explorers of the Mediterranean, who

spread it to Greece; Greek writing inspired numerous systems on the

Italian peninsula, that would eventually give rise to Latin, and the

Roman Empire's conquests throughout Europe made it the dominant

writing system on the continent. In the east, Phoenician was also an

ancestor of Aramaic, which was the basis of Arabic; Arabic in turn

became the basis for Persian and Urdu scripts used in Iran and

Pakistan. Some suspect that Phoenician is also the basis of writing

in India. Since Indian writing systems are used from Central to

Southeast Asia, if this is true, it means almost everyone on Earth

writes in a script descended from Phoenician.

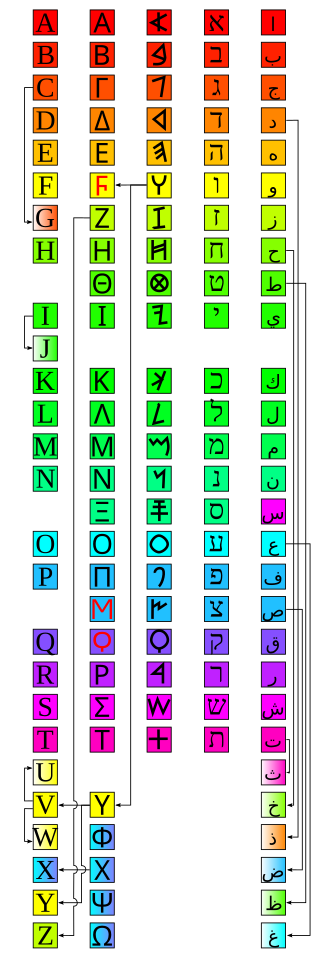

|

| This diagram shows how some major alphabets descended from Phoenician. The column in the middle is the Phoenician alphabet. To its left, you can see the letters of the Greek alphabet, and how they were based on Phoenician writing, and to the left of that, the Roman alphabet, based on Greek. On the right, you can see first the Hebrew alphabet, then Arabic. |

That

is a very brief history of how letters came to be. I haven't

even talked about lowercase letters, invented in the Middle Ages to

be easier to write with a pen. I encourage you to do more research on

this fascinating topic, but do want to quickly discuss what I

mentioned in the beginning: there are some cases where a single

person did "invent" letters.

Many

of these were still based on previous writing systems: Cyrillic, the

alphabet used in Russia and much of Eastern Europe, was created a by

a team of scholars and based mainly on Greek. The Armenian alphabet

was developed by a single linguist around 400 AD, and seems to be

based on Greek and Persian alphabet. In 1821, a Cherokee linguist

named Sequoyah developed the first writing system for Cherokee, based

on Latin letter forms.

Alphabets

that are purely invented without previous reference are called

constructed

alphabets,

and are usually made for fun, or as a work of art, like J. R. R.

Tolkien's alphabets

for his fictional Elvish languages. Sometimes, people construct

alphabets because they think the current one is too confusing: the

playwright George Bernard Shaw wanted

people to use his

Shavian

alphabet, which

he thought made more sense than the Latin one.

There is only one example of a constructed alphabet being

widely used for a real language,

and that's Hangeul,

the writing system for Korean.

.jpg) |

| This is a page from an early guide on how to read Hangeul. The simple, geometric shapes are the Hangeul letters, and the Chinese characters explain how to use them. |

Chinese,

in much the same way that hieroglyphics were used for writing Semitic

languages; characters were used to represent sounds without much

regard for meaning. Languages like Japanese adapted and modified

Chinese characters to fit their language, but a Korean king named

Sejong the Great decided that to promote literacy in his realm, he

needed a perfectly logical alphabet completely suited to the Korean

language. In 1443, a team of scholars assembled by Sejong completed

Hangeul, a writing system that has been recognized the world over for

its clarity and logic; each consonant represents the shape of the

tongue in the mouth, while each vowel reflects the philosophical

ideals of the kingdom. This makes Korean the only language with an

alphabet completely unrelated to any other!

For

more information on alphabets, you can check out Omniglot,

an online encyclopedia of languages and writing systems. And to learn

more about Egyptian hieroglyphics, look at this

post on the Cambridge Science Festival blog!

------------But what about numbers? We're not finished yet!

The

simplest way of recording numbers is a unary system, in which

each mark (a numeral) represents an object being counted. The

number two? Two marks. The numbers seven? Seven marks. This system is

easy to learn and understand, and very sufficient for writing small

numbers. The trouble comes when you want to record a number higher

than humans can easily count. Writing down two hundred marks isn't

just tiring, it takes just as long to read as to write; you can't

tell at a glance the difference between two hundred markings and two

hundred and ten.

Still,

this system is still widely used for counting small numbers; around

the world, people use different

kinds of tally

marks to keep score in games. And believe it or not, unary

numbers were the basis of the most popular number systems in the West

for over a thousand years: Roman

numerals. Though there are a couple of fancy rules involved in

Roman numerals to make them shorter to write down, the principle is

the same as any unary system: to read the number, add up the

numerals. X is ten, V is five, and I is one: XXVI is ten + ten + five

+ one = twenty-six.

Learning to read Roman numerals can be cool if you want to translate inscriptions on old buildings, but it's not very useful in the modern world. Like all counting systems based on a unary model, it's hard to use with high numbers; the highest symbol in Roman numerals is M, for a thousand, so any number of multiple thousands will take a long time to write. Addition and subtraction are pretty easy, but multiplication is a chore, and division is... well, I'll include a link explaining division at the end, but let's just say it's no fun. These days, we use a positional number system instead.

In a positional system, you don't just add up each numeral; the position of a numeral affects its value. We write twenty-six as 26, the numeral 2 followed by the numeral 6. But because of the 2's position, we know it doesn't really mean "two," it means "twenty": two times ten. Who invented this system?

Like writing, positional numbers were likely invented in two separate locations: both ancient Chinese and Indian civilizations used similar positional number systems. However, the Indian system was more comprehensive: the Indian mathematician Brahmagupta was the first to treat the numeral zero as a number like all the rest, and it is this system that forms the basis of our modern writing system. Ancient Indian mathematicians had a tremendous impact on math: algebra, trigonometry, and negative numbers were all perfected during the Golden Age of Indian mathematics, from roughly 400 to 1600 CE.

Learning to read Roman numerals can be cool if you want to translate inscriptions on old buildings, but it's not very useful in the modern world. Like all counting systems based on a unary model, it's hard to use with high numbers; the highest symbol in Roman numerals is M, for a thousand, so any number of multiple thousands will take a long time to write. Addition and subtraction are pretty easy, but multiplication is a chore, and division is... well, I'll include a link explaining division at the end, but let's just say it's no fun. These days, we use a positional number system instead.

In a positional system, you don't just add up each numeral; the position of a numeral affects its value. We write twenty-six as 26, the numeral 2 followed by the numeral 6. But because of the 2's position, we know it doesn't really mean "two," it means "twenty": two times ten. Who invented this system?

Like writing, positional numbers were likely invented in two separate locations: both ancient Chinese and Indian civilizations used similar positional number systems. However, the Indian system was more comprehensive: the Indian mathematician Brahmagupta was the first to treat the numeral zero as a number like all the rest, and it is this system that forms the basis of our modern writing system. Ancient Indian mathematicians had a tremendous impact on math: algebra, trigonometry, and negative numbers were all perfected during the Golden Age of Indian mathematics, from roughly 400 to 1600 CE.

|

| Numeral systems from around the world, all based on the original Indian numbers |

But

while Indian cultures used a positional number since at least 700 CE,

it wouldn't spread to Europe until the Middle Ages. The person most

associated with Indian numerals in the West is mathematician Leonardo

Bonacci, or Fibonacci,

who introduced the new system of writing numbers to Europe in 2012.

He had learned the numerals from traveling about the Mediterranean

and meeting Arabic traders, who had learned it from the studies of

Persian mathematical genius al-Khwarizmi.

For this reason, the numbers used in the West are sometimes called

"Arabic numbers," even though Arabic-speaking countries

call their numbers "Hindi numbers."

Again,

this is

an extremely brief summary! I didn't even mention some of the most

interesting writing systems in history, the Babylonian and Mayan

systems! You may not have thought that such a simple question would

take so long to answer, but that's the strange thing about the

history of science: sometimes the most simple ideas take the longest

time to establish. The alphabet and numerals we use today seem

perfectly natural to us, but they were created by complicated and

messy cultural changes. It's one of the reasons history is so

interesting: you get to see the weirdness hiding behind everything we

see as ordinary.

For

more information on numbers, there's no better resource than Isaac

Asimov's Asimov

on Numbers (ISBN:

067149404X).

To learn how to divide using Roman numerals, start with mathematician

Lawrence Turner's page here.

--------Ben Tolkin once spent a summer teaching himself Elvish. His recommended strategy for learning important things is to ask the questions so obvious no one can think of an answer to them.

Very wonderful blog.The writing company should be collect real types of data and online based information .

ReplyDelete